Laws and policies promoting gender equality in education are inadequately implemented

2020 Gender Report

Credit: Mohammad Rakibul Hasan

Laws and policies determine the framework for achieving inclusion in education. At the international level, the global community’s aspirations are expressed in binding legal instruments and non-binding declarations, primarily led by the United Nations but also by regional organizations. These agreements have strongly influenced the national legislative and policy actions on which progress towards inclusion hinges.

However, in spite of the good intentions enshrined in laws and policies on inclusive education, governments often do not take the follow-up actions necessary to ensure implementation. Barriers to access, progression and learning remain high, and they disproportionately affect more disadvantaged populations. Within education systems, these populations face discrimination, rejection and reluctance to accommodate their needs. This section gives a brief overview of key international instruments and examines the evolution of legislative and policy development on two areas with a bearing on gender equality in education: early pregnancy and school counselling.

INTERNATIONAL INSTRUMENTS HAVE SHAPED INCLUSION AND GENDER EQUALITY IN EDUCATION

The 1979 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action have been and continue to be influential in driving legislative initiatives towards gender equality around the world. In the past decade, 131 countries have enacted 274 legal and regulatory reforms supporting gender equality. In 80% of the countries with data, national plans to achieve gender equality are in place, although only one-third are costed and resourced (UN Women, 2020a).

Progress has been made towards eliminating gender discrimination in education. Building on the 1960 UNESCO Convention Against Discrimination in Education, which has been ratified by 23 more countries since 1995 for a total of 105 (UNESCO, 2020d), Article 10 of CEDAW asks signatories to ‘take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in order to ensure to them equal rights with men in the field of education’. Yet many countries entered reservations when ratifying CEDAW (Keller, 2014). Over time, all reservations on Article 10 have been withdrawn, but many reservations remain on other articles limiting the education opportunities of women and girls (Freeman, 2009).

Overall, 90 countries now prohibit gender discrimination in their constitutions. An analysis by the GEM Report team shows that education ministries have sponsored laws promoting gender equality in 50% of countries and have issued policies to that end in 42% of countries. Another 46% of countries have legislation and 58% policies promoting gender equality in education under other ministries’ leadership.

Education ministries have sponsored laws promoting gender equality in 50% of countries and have issued policies to that end in 42% of countries

The right to inclusive education is enshrined in the 2006 UN Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. In 2016, General Comment 4 by the UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities broadened the concept of inclusion, stating that among the core features of inclusive education must be respect for the diversity of all learners, irrespective not only of disability but also of other characteristics, such as sex. Still, many governments have yet to establish this principle in their laws, policies and practices: 68% of countries have a definition of inclusive education in their laws and policies but only 57% of these definitions cover multiple marginalized groups. In 25% of countries, the definition of inclusive education only covers people with disabilities or special needs.

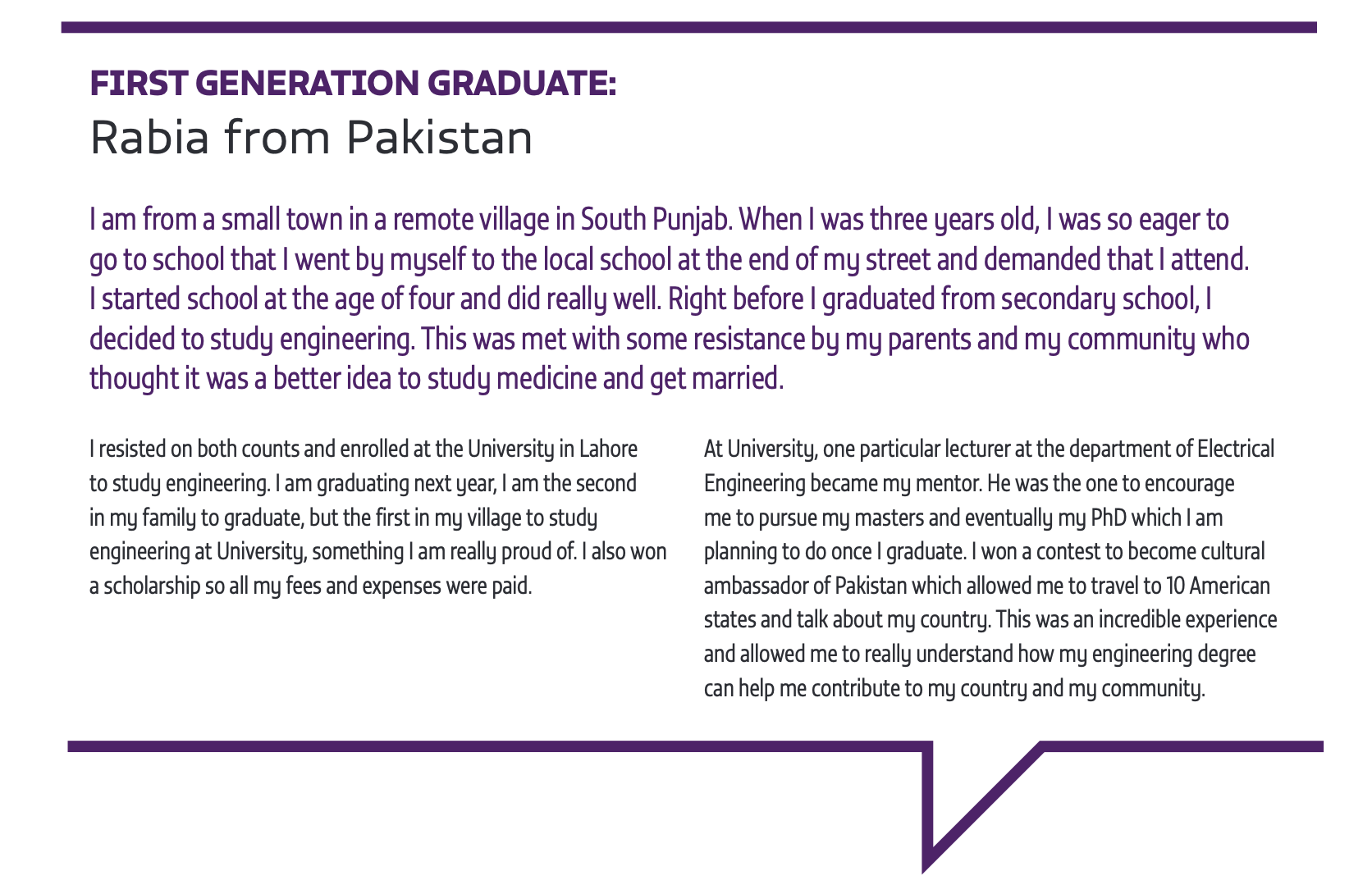

EDUCATION POLICIES AND PRACTICES CONTINUE TO FAIL GIRLS WHO EXPERIENCE EARLY PREGNANCY

Early or teenage pregnancy can be a consequence of early school leaving, but it is also one of its causes: pregnant girls and young mothers are not always able to return to school to continue or complete their education, especially in poorer countries, but also in some rich ones. Strategic objectives B.1 and B.4 of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action called on countries to remove all barriers to formal education for pregnant adolescents and young mothers, including by promoting affordable and physically accessible childcare facilities and parental education to encourage those responsible for the care of children and siblings to return to, continue and complete their education.

Early pregnancy rates remain at levels higher than the 1995 regional average in some sub-Saharan African countries

Globally, the prevalence of early pregnancy declined by one-third between 1995 and 2020, from some 60 to 40 births per 1,000 women aged 15 to 19 (UNPD, 2019). Yet early pregnancy rates remain high in many countries, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, where, despite an overall fall from 133 to 97 births per 1,000 15- to 19-year old women over the past 25 years, rates remain at levels higher than the 1995 regional average in countries including Chad (145), Mali (157) and Niger (171). Early pregnancy is often linked to early marriage (Box 5).

Case studies from Argentina (Ginestra, 2020a), Sierra Leone (Bah, 2020) and the United Kingdom (Freedman, 2020) show how early pregnancy hinders girls’ education, and what steps have been taken to ameliorate the problem. Strong political commitment has led to progress in reducing early pregnancy rates and providing education for pregnant girls. Support to pregnant teenagers to address issues with childcare and with social, health and psychological problems has to be holistic to keep them in education. It requires cross-government cooperation, backed up with adequate funding and coordination with partners.

In Argentina, legislation and flexible programmes have supported pregnant girls and young parents

Argentina recorded 61 births per 1,000 women aged 15 to 19 in 1995; the figure had fallen to 49 by 2018. An initial decline was followed by an increase between 2003 and 2011, then the rate decreased again. Most early pregnancies occur among 15- to 19-year-olds but pregnancies among younger girls also exist. The number of births per 1,000 girls below 15 fell from 2.1 in 1995 to 1.4 in 2018 (Ginestra, 2020a). The probability of early pregnancy depends on region, education level, socio-economic status and access to sexual and reproductive health education and services. In 2011/12, 18% of the poorest 20% of women aged 15 to 19 were pregnant, compared with 3% of the richest 20% (UNICEF and Argentina Ministry of Social Development, 2013). As of 2017, young mothers represented 4.4% of students in urban areas but 8.7% in rural areas. Young fathers represented 3.1% of students in urban areas and 4.5% in rural areas (Argentina Ministry of Education, 2017). Girls’ risk of early pregnancy is increased by poverty, limited access to adequate health services, low school retention rates, work at early ages, childcare responsibilities and general inequality of opportunity (Azevedo et al., 2012).

For girls aged 15 to 17 who had attended school, maternity was the main reason for early school leaving, cited by 38% (UNICEF and Argentina Ministry of Social Development, 2013). Among 15- to 29-year-olds of both sexes, about 16% said pregnancy, maternity, paternity or engagement was their main reason for not completing secondary school. However, while 30% of females mentioned dropping out due to maternity, only 5% of males cited paternity as the reason (INDEC, 2014).

The proportion of pregnant girls and young mothers decreases as the level of education attained increases (UNICEF and Argentina Ministry of Social Development, 2013). While 57% of young mothers had completed primary and 38% had completed secondary, only 4% had continued into post-secondary education. Conversely, 55% of 20- to 29-year-old women who had not experienced early pregnancy had completed secondary education and 15% had continued their studies beyond secondary (UNFPA, 2020).

Pregnancy during adolescence also has a detrimental effect on school achievement. Pregnant girls and young mothers achieve lower grades and fail more often than girls without children. For instance, 64% of young mothers did not achieve basic proficiency in mathematics, compared with 45% of other female students. Young parents are also more likely to repeat grades (Argentina Ministry of Education, 2017).

Paternity in adolescence has received much less attention than maternity. Qualitative studies have struggled to reach a consensus on its impact. Some research indicates that young fathers leave school to provide for their children (Fernandez Romeral, 2017), while other studies suggest that most had already left school and that the pregnancy encouraged them to re-enter school (Argentina Ministry of Education, 2019).

Argentina has enacted two laws that protect pregnant girls’ and young parents’ right to education. Its 2002 Law 25584 prohibits any institutional action that prevents pregnant students and young mothers and fathers from school entry or continuation. They have the right to permitted absences during pregnancy, breastfeeding or any matter related to the health of mother or child (Argentina Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, 2002). Law 26206 in 2006 guaranteed school entry, progression and completion for female students during and after pregnancy, making available breastfeeding rooms, home- and hospital-based education, special regimes of absences and flexibility with regard to examinations. It also made it possible for young mothers to attend classes with their child and envisaged including out-of-school adolescents in non-formal education before full reintegration in formal school (Argentina Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, 2006).

Flexible learning programmes at the provincial level have enabled pregnant girls and adolescent parents to return to school. In 2008, Buenos Aires province introduced the programme Salas maternales: madres, padres y hermanos/as mayores, todos en secundaria (Nurseries: mothers, fathers and siblings, all in secondary school) in cooperation with UNICEF. Nurseries are set up in schools that can accommodate them or in nearby kindergartens. While students attend classes, their children receive care in an environment that stimulates early learning. At school, adolescent parents receive support to help them carry out their role as parents or caregivers and continue studying. In 2017, there were 82 nurseries across the province. An evaluation found that school retention had increased, generating higher school completion without interruption. Furthermore, young parents’ attitudes towards studying had changed, with school completion seen as allowing adolescents to be independent of their families, find a good job and begin university. The programme is unique in also targeting young fathers (UNICEF, 2017). The Autonomous City of Buenos Aires has also implemented interventions to address the education implications of early pregnancy (Box 6).

Sierra Leone overturned an education ban on pregnant girls and young mothersIn Sierra Leone, the percentage of 15- to 19-year-olds who have given birth fell from 34% in 2008 to 21% in 2019. More rural teenagers (29%) than urban (14%) have early pregnancies, and teenagers from the poorest 20% of households (33%) are more likely than their richest counterparts (11%) to have children. Early pregnancy rates decrease with education: 44% of adolescent girls with no education have already had a child, compared with 17% of those with secondary education.

In Sierra Leone, at least 20% of school-age girls are not in education because of pregnancy

At least 20% of school-age girls are not in education because of pregnancy (Statistics Sierra Leone and ICF, 2019). When pregnant girls leave school, it is rarely due to lack of motivation or interest. Instead, it is because they lack social support, childcare assistance and legitimate financial means to support themselves. They may become more dependent on men, which increases the risk of rapid repeat pregnancies, jeopardizing their health and that of their children.

Forced exclusion during pregnancy has been a long-standing practice, rooted in societal gender norms and cultural practices. Reports of degrading treatment of girls, such as urine testing and physical examinations in schools, exist have existed since at least the 1990s. Before 2010, expulsion was widespread but not universal; many schools and head teachers did allow girls to stay in school and take examinations, and there was no written policy or ban stopping pregnant girls from attending school, although dealing with negative teacher, peer, parent and community attitudes and behaviours on teen pregnancy was challenging.In August 2010, however, Sierra Leone’s cabinet agreed that the minister of education, youth and sports should issue a directive preventing pregnant girls from attending school and taking examinations. The ban became official policy in April 2015, just as schools reopened after the 2014 Ebola outbreak. It remained operational until 2019. At that time in sub-Saharan Africa, Sierra Leone, Equatorial Guinea and the United Republic of Tanzania totally banned pregnant girls and young mothers from public schools (Human Rights Watch, 2019). In addition, 20 countries had no laws, policies or strategies supporting girls’ right to go back to school after pregnancy (Human Rights Watch, 2018).

Activists brought a case against Sierra Leone at the Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States, which ruled the ban discriminatory in December 2019 and ordered its immediate lifting. In March 2020, the government complied, overturning the 2010 ban and announcing two new policies focusing on ‘radical inclusion’ and ‘comprehensive safety’ of all children in the education system, to take effect from the 2020/21 school year (Sierra Leone Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education, 2020).

In the United Kingdom, tackling early pregnancy required cooperation between government departments

The early pregnancy rate has more than halved in the United Kingdom: the number of conceptions per 1,000 women aged 15 to 17 declined from 42 in 1995 to 18 in 2017, although the level is still above that in other western European countries. Section 7 of the 1996 Education Act requires parents of young women who become pregnant while in school to make sure their daughter receives a full-time education until she turns 16.

However, despite the legal framework, many adolescent girls who become pregnant are still de facto excluded from education institutions because of lack of access to childcare or school facilities, as well as discriminatory and stigmatizing attitudes. Women who have children before 18 are 20% more likely than other women to have no education qualification by age 30 (Cook and Cameron, 2015). The combination of lack of education qualifications and the demands of motherhood results in lower employment opportunities and higher likelihood of living in poverty (Department for Children, Schools and Families, 2007).

In the UK, women who have children before 18 are 20% more likely than other women to have no education qualification by age 30

The Teenage Pregnancy Strategy, which ran from 1999 to 2010, was an important initiative to address early pregnancy and meet young parents’ needs. Part of broader efforts to tackle social exclusion, it took a wide-ranging, holistic approach. It included a national awareness-raising campaign; better coordination between government departments and tiers; improved prevention of the causes of teenage pregnancy through measures such as better education in and out of school, access to contraception and targeting of at-risk groups, including young men; and a focus on young mothers’ return to education through childcare support. A national and local structure was set up to implement this strategy, including a national Teenage Pregnancy Unit established with cross-government funding and consisting of a team of civil servants and external experts from the non-government sector.

Comprehensive sexuality education is crucial in addressing early pregnancy

While most early pregnancies occur within marriages or unions, their prevalence can indicate lack of access to sexual and reproductive health education and services to prevent unwanted pregnancies. Global evidence shows that comprehensive sexuality education programmes can help young people to choose to delay having sex, reduce the frequency of unprotected sexual activity and increase the use of protection against unintended pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (UNESCO, 2018).

In Argentina, 83% of female and 74% of male secondary school students reported in 2017 that the subject they would most like the school to address was sexual and reproductive health (Argentina Ministry of Education, 2017). Such education has been compulsory in public and private schools at all levels since 2006, and a National Programme of Comprehensive Sexual Health Education began in 2008 (Argentina Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, 2006). However, as evidenced by the students’ responses, provision in schools is still variable and only partial. Out of 23 provinces, 16 adhered to the national law or had passed their own legislation; Formosa, Mendoza and Jujuy had ministerial resolutions instead of provincial laws; Córdoba formed a commission to boost provision of sexual and reproductive health education in schools and created a provincial programme in 2009; and Salta, Santiago del Estero, Tucumán and Tierra del Fuego had no sexual and reproductive health education legislation, even though their early pregnancy rates are among the country’s highest.

The high number of religious (mostly Catholic) schools opposed to the law is a key obstacle to implementation. Some provincial governments have also lacked political commitment for religious reasons. Inconsistency in provincial education laws regarding religious education contributes to unequal provision of sexual and reproductive health education: while some provinces encourage Catholic education in schools, others support pluralistic, non-dogmatic, scientific and secular education. Moreover, the national law on sexual and reproductive health education is somewhat ambiguous. Although it establishes binding curriculum content for each education level, it says each school can adapt the content depending on its sociocultural contexts, ideologies and beliefs, with no explanation of how they should be reconciled (Esquivel, 2013).

Argentina has a remarkable range of measures intended to guarantee adolescents’ right to sexual and reproductive health services. However, some are only partially implemented, while others lack accountability and transparency mechanisms (Human Rights Watch, 2010).

Knowledge and access to contraceptives continue to be huge challenges for girls and women in Sierra Leone. Between 2008 and 2013, the share of married and sexually active women aged 15 to 19 using modern means of contraception doubled from 10% to 20%. By 2019, however, a precipitous drop to 14% had taken place, possibly associated with a 2008 government decision to essentially end comprehensive sexuality education in schools. Reduced access to services across the country due to the Ebola outbreak may have been a further factor (Bah, 2020), a concern exacerbated by the school closures due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Box 4).

In the United Kingdom, the 2017 Children and Social Work Act introduced compulsory relationship education in primary schools and compulsory relationship and sex education in secondary schools from September 2019. Statutory provision was expected to start in September 2020, with guidance applying to all schools, including free schools, academies and faith schools. The guidance obliges schools to increase the time spent teaching about menstrual health and informed consent, addresses risks related to social media and the internet, such as sexting and image-based sexual abuse, and outlines what pupils should know at the end of each level of schooling. Two parents’ guides were published so that schools could engage with parents to try to avoid resistance to relationship and sex education.

For the next generation of girls, I wish for less taboos! Let’s talk about sex! Let’s talk about contraception! Let’s talk about pregnancy! Let’s talk about menstruation! Let’s talk about gender! Let’s talk about FGM and GBV! Let’s talk! Openly. Together. And without shame.Corinna, Netherlands

SCHOOL COUNSELLING POLICIES HAVE NOT BEEN SUFFICIENTLY GENDER-RESPONSIVE

Strategic objective B.1 of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action called on countries to make available non-discriminatory and gender-sensitive professional school counselling and career education to encourage girls to pursue academic and technical curricula in order to widen their career opportunities and ensure equal access to education. The influence of teaching practices and teachers’ perceptions on girls’ and boys’ school orientation has been well studied, but the role of school counsellors and the extent to which countries have made this institution more gender-responsive have been less frequently considered.

As part of a general support system, counsellors can play an important role in steering young people towards tertiary education and helping them make the best choices for their future studies and career. Yet too few students benefit. In the United States, the median number of students per counsellor is 455, nearly twice the recommended level of 250 (American School Counselor Association, 2019; Chrisco Brennan, 2019). Access to counsellors is even more limited in France, with 1,200 students per counsellor in some secondary schools (Mayer, 2019). High workloads limit advisers’ time with students and their ability to provide academic guidance. A 2018 survey by the National Council for School System Evaluation showed that half of 18- to 25-year-olds were dissatisfied with the counselling they had received in secondary school and did not feel supported by the institution at this critical stage (Hoibian and Millot, 2018).

Recognizing and accepting diversity is another important challenge. Counsellors’ perceptions, sociocultural biases and gender stereotypes can affect students’ education and career choices (United States Department of Education, 2018). An online random survey of secondary school counsellors in the US state of Wisconsin found that, even when school counsellors believed female students outperformed males in mathematics and were more likely to succeed, they were less likely to recommend mathematics over English to female students (Welsch and Windeln, 2019).

School and career counselling frequently lack gender responsiveness. Initiatives and programmes to help students make informed choices, free of gender bias, about their future fields of study and career frequently come from outside of education systems. This is confirmed by case studies of Botswana (Mokgolodi, 2020), Germany (Faulstich-Wieland, 2020) and the United Arab Emirates (Labib, 2020).

Gender patterns in TVET and STEM enrolment have evolved to varying degrees over the past 25 years, and countries have adopted a variety of approaches on using school counselling to orient more girls and women towards TVET and STEM.In Botswana, the overall share of women in TVET increased marginally over 1995–2018, from 31% to 35%. Their numbers also remain low in STEM subjects, despite improvement over the period. In recent years, women have outnumbered men in tertiary education: in 2017, they accounted for 59% of the student population. However, in 2018 women still made up a lower share of those enrolled in science (40%), and even lower in engineering, manufacturing and construction (29%).

A Gender Reference Committee was set up in 2006, with representation from all departments of the Ministry of Education and Skills Development to conduct gender awareness campaigns and make education gender-sensitive. Its work was guided by recommendations made in the 10th National Development Plan and the 1994 Revised National Policy on Education, which advocated for inclusive education and career guidance for the world of work (Botswana Ministry of Education, 1994; 1996). Since 1995, a comprehensive and compulsory guidance and counselling programme, which includes material on gender stereotypes, has been offered at all levels from pre-primary to tertiary education (Gysbers and Henderson, 2014). Its curriculum was developed in 1995, and pre-service and in-service guidance and counselling training was offered to teachers.

In 2011, the Gender Reference Committee revisited its strategy to enhance female participation in traditionally male-dominated careers and improve stakeholders’ understanding and participation. It developed a policy, an action plan and a poster campaign. In partnership with industry and tertiary education institutions, it organized science and mathematics fairs, career fairs, and forums on girls in mathematics and science to change views about careers and gender. The Human Resource Development Council, the semi-autonomous body responsible for skills development in the country, provides annual training to help school and career counsellors provide career guidance free of gender bias and stereotypes. Despite these coordinating structures, policies, plans and initiatives, an overall framework on how to facilitate inclusion of girls and women into TVET and STEM is lacking.

In Germany, the share of girls in STEM increased from 12% in 1999 to 19% in 2017. Germany is a federal republic in which the states are in charge of education. Schools have been responsible for providing counselling for vocational or career orientation and guidance since 2010. However, gender aspects are not central to these measures, and regional education authorities leave it up to individual schools, teachers or counsellors as to how and whether to conduct gender-responsive activities. School counselling does not seem so far to have much effect on the career directions of girls and women.

However, two nationwide activities supported by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research aim to improve the situation. The first, Komm-mach-MINT (Come do STEM) is an online platform intended to support girls and women in choosing further study and careers. It provides information on STEM for secondary and university students, parents, teachers and organizations (National Pact for Women in STEM Occupations, 2019; Großkopf and Struwe, 2019). The second, Klischeefrei (Cliché free), is a collaboration between the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth and the Federal Ministry for Employment and Social Affairs. Launched in December 2017, it aims to remove gender stereotypes in all career and study paths for girls and boys starting from the pre-primary level all the way up to university and employment. It offers material for teachers and counsellors to use in their classes In the United Arab Emirates, women’s access to and participation in TVET and STEM grew between 1995 and 2017. However, women are still under-represented, particularly in engineering and construction. While the share of men and women is equal in ICT, female students are over-represented in certain STEM fields, including health and mathematics.

The government has developed education infrastructure and initiated national strategies to promote STEM and TVET education for boys and girls. The Ministry of Education Strategy 2010–2020 introduced a formal student counselling structure and programme to be implemented in schools (UAE Ministry of Education, 2020). In 2014, the National Admissions and Placement Office of the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research began providing annual academic counselling for secondary school students and their parents in public and private schools (UAE Ministry of Education, 2014, 2015). However, neither the strategy nor its implementation makes any reference to gender or to whether programmes and counsellor training and support include gender-responsive practices. The same is true of more recent policies and long-term plans drafted at the federal level, including the Education 2020 Strategy, UAE Vision 2021, National Strategy for Higher Education 2030 and 2018 National Strategy for Advanced Innovation.

One gender-focused initiative is a collaboration between the Dubai Society of Engineers, a semi-government body which plays an active role in engaging Emirati women in science, technology, engineering and robotics, and the national section of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Women in Engineering Committee, which coordinates events and activities to inspire and engage young female Emirati students in STEM fields (Margheri, 2016).

Countries need to include mandatory gender-responsive school counselling and career orientation to deconstruct false images of technology and their biased connection to gender stereotypes

Countries need to include mandatory gender-responsive school counselling and career orientation to deconstruct false images of technology and their biased connection to gender stereotypes. Such measures should nurture girls’ talents and interests in STEM and TVET. A key element of this kind of gender-sensitive orientation is professional training in gender-responsive guidance for teachers and counsellors (Driesel-Lange, 2011). Career guidance programmes should aim to raise awareness among parents, the most influential socialization agents, to enable them to play supportive roles free of biased notions of gender-appropriate careers. Hands-on experiences and internships can allow female students to see that their skills are valuable in technical occupations (Neuhof, 2013). The impact of school counselling necessarily has limitations, since it cannot change labour market realities where the responsibility for hiring lies with companies, but it can play an important part in encouraging young women and girls to break through barriers and fulfil their potential in traditionally male-dominated fields.