CREDIT: Christopher Herwig / UNICEF

In an inclusive school, all students are welcome, feel they belong, realize their potential and contribute to daily school life. Inclusive schools ensure that all students, regardless of background, ability or identity, are engaged and achieving by being present, participating and learning. However, many schools fall short, including in terms of gender inclusion, for reasons ranging from poor infrastructure to unsafe learning environments.

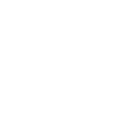

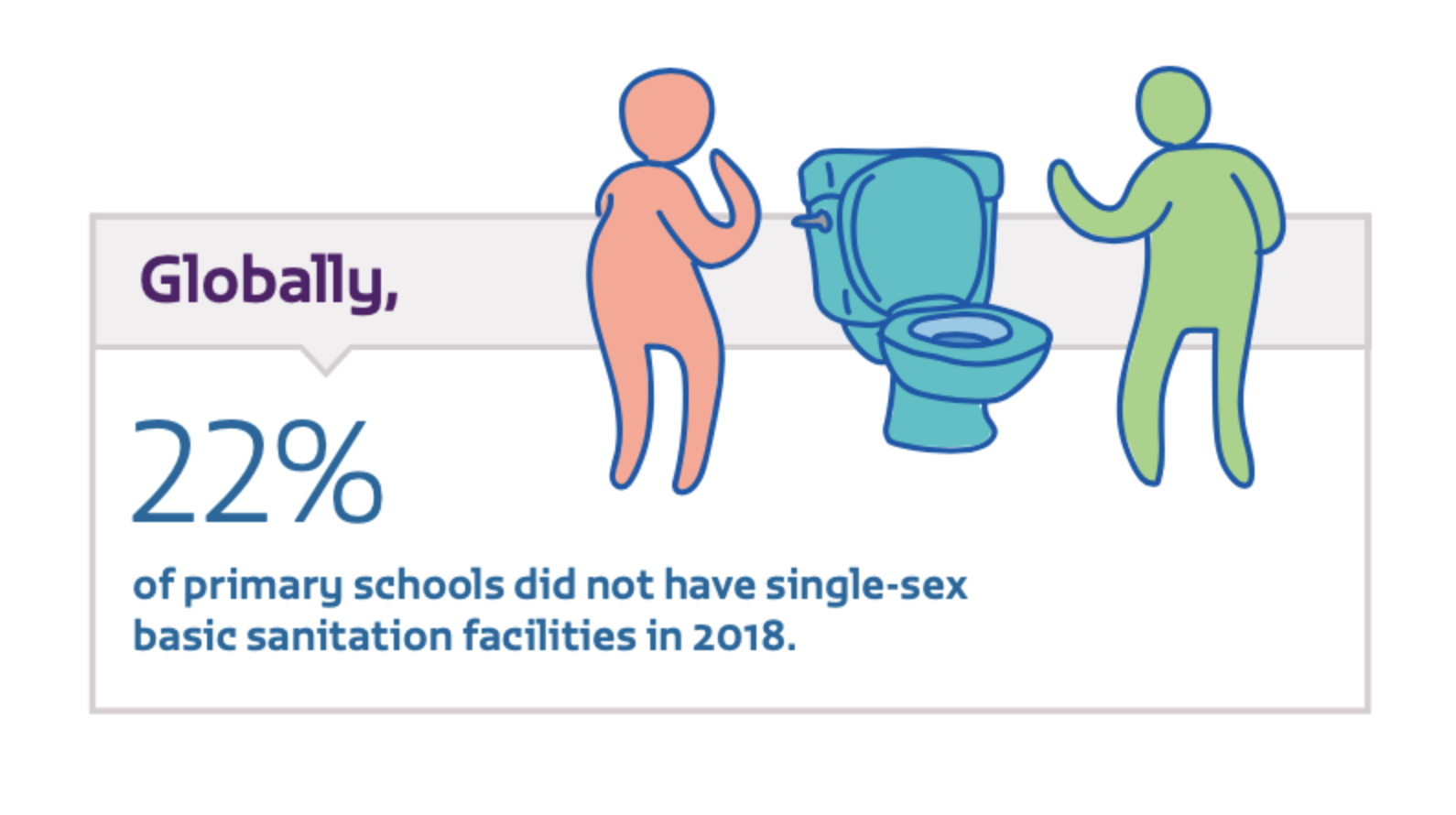

Globally, 78% of primary schools had single-sex basic sanitation facilities in 2018, although availability varies by education level; facilities are less common in primary than secondary schools, with a gap of over 10 percentage points at the global level. In Afghanistan, Jordan and Senegal, the percentage of upper secondary schools with single-sex toilets is about three times that of primary schools (Figure 16). Overall, some 335 million girls attend primary and secondary schools lacking facilities essential for menstrual hygiene (UNICVEF, 2019).

Figure 16: Fewer primary schools have single-sex toilets

The Philippines has had challenges in ensuring adequate menstrual hygiene management (Harver et al, 2013). According to the UIS database, just 39% of schools had basic sanitation and 46% had basic hygiene facilities in 2016. The Department of Education monitors implementation of its 2016, which committed schools to ensuring that menstrual hygiene management conditions were met. More than one-third of 35,000 schools did not have water during all school hours in 2018/19. Moreover, on average, there are 125 girls per functional toilet, much higher than the national standard of 50 students per toilet. However, improvements were reported relative to 2017/18 with respect to quality indicators such as lighting, ventilation, security and privacy, as well as availability of wrapping materials and disposal facilities (Philippines Department of Education, 2020).

Even where single-sex sanitation facilities exist, they may not be accessible to all students. The WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme database, which provides information on accessibility for students with disabilities in 18 countries, reported that less than 1 in 10 schools with improved sanitation had accessible facilities in El Salvador, Fiji, Tajikistan, the United Republic of Tanzania and Yemen

The 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action called upon governments to ‘take measures to eliminate incidents of sexual harassment of girls in educational and other institutions’

SCHOOL-RELATED GENDER-BASED VIOLENCE UNDERMINES INCLUSIVE EDUCATION

Gender-based violence remains pervasive, even though less than 40% of women who experience it report it or seek help (UN Women, 2020c). School-related gender-based violence consists of acts or threats of sexual, physical or psychological violence occurring in and around schools, perpetrated as a result of gender norms and stereotypes and enforced by unequal power dynamics (UNESCO and UN Women, 2016). In strategic objective L.7, the 1995 Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action called on governments not only to ‘take effective actions and measures to enact and enforce legislation to protect the safety and security of girls from all forms of violence at work, in training and support programmes’ but also to ‘take measures to eliminate incidents of sexual harassment of girls in educational and other institutions’.

In spite of this commitment, millions of female and male children and youth experience gender-based violence in and around schools and online. Girls are more likely to experience verbal and sexual harassment, abuse and violence, while boys are more often subject to physical violence, including corporal punishment.

In many surveys, physical appearance is the most common reason for bullying, with female students more at risk of being bullied for this reason (UNESCO, 2019a). In Argentina, obese 9- to 10-year-old children were at significantly higher risk of bullying, with boys more common victims of physical bullying than girls (Kovalskys et al., 2016). In the United States, 30% of overweight girls and 24% of overweight boys in the final year of primary school had daily experience of teasing, bullying or rejection due to their size, with the rates rising to 63% for girls and 58% for boys in secondary school (Stevelos, 2011). Self-perception as underweight or overweight and dissatisfaction with personal appearance are positively correlated with the experience of bullying. Adolescent girls are more likely than boys to perceive themselves as overweight (Lin et al., 2017).

Girls are the main victims of unwanted sexual touching and non-consensual sex attempts perpetrated by classmates and teachers, respectively. In sub-Saharan Africa, girls reported that male teachers demanded sexual favours in exchange for good grades, preferential treatment in class, money and gifts (VACS, 2020). In Ghana, Kenya and Mozambique, girls reported it was difficult to decline teachers’ proposals as they feared retaliation (Heslop et al., 2015).

Violence is often directed at lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender students and other learners who exhibit non-binary gender identities. In the United Kingdom, 45% of lesbian, gay and bisexual students and 64% of transgender students were bullied in schools (Bradlow et al., 2017). In the United States, 17% of heterosexual students reported having been bullied, compared with 24% of those unsure about their gender identity and 33% of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex students (CDC, 2017).

Technology has opened up new spaces in which children and youth are threatened, intimidated and harassed. In EU countries, one in five 18- to 29-year-olds reported having experienced cyber-harassment (UN Women, 2020b). Data from the 2013/14 WHO Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (UNESCO, 2018) and the more recent Global Kids Online project (covering Bulgaria, Chile, Ghana, Italy, Montenegro, New Zealand, the Philippines, South Africa and Uruguay) (UNICEF, 2020) show that girls especially suffer from violence online. Global Kids Online found that 54% of girls experienced online harassment, compared with 48% of boys. Among victims, 36% reported that the incidents occurred on social networks such as Facebook and Twitter, 18% reported harmful text messages and 14% said they received bullying mobile phone calls. Girls were more likely to be treated in a hurtful or nasty way via social networks (38%), text messages (21%), mobile phone calls (16%) and chat rooms (5%) while boys reported more mistreatment in online games (10%) and on media-sharing platforms (5%) such as YouTube, Instagram and Flickr (Global Kids Online 2020; Ginestra, 2020b).

School-related gender-based violence damages well-being and learning

School-related gender-based violence undermines the achievement of inclusive and equitable education of good quality for all children and young people. Consequences may include severe health and psychological harm, pregnancy, HIV or other sexually transmitted infections. Violence can lead to loss of interest in school, disrupted studies or early school leaving. In Honduras, 55% of girls reported not attending school at some point due to physical violence perpetrated by teachers, while 22% of female students in Malawi reported missed school due to unwanted sexual experiences (VACS, 2017). For victims who continue their studies, low achievement is common, as they try to avoid attention from teachers and peers (Ginestra, 2020b). According to 2018 PISA data, bullied students in OECD countries scored 21 points lower in reading on average than their peers who had not been bullied (OECD, 2019c).

Countries have introduced laws, policies, programmes and initiatives to combat school-related gender-based violence. In Namibia, the Ministry of Education, Arts and Culture, with the support of UNICEF, introduced a National Safe Schools Framework in 2018 including seven safe learning and teaching space standards. One refers to prevention of and actions against violence and self-harm through maintaining safe schools and encouraging the school community to report violence. National frameworks of this kind need to be translated into local action. However, experience in Ghana, Kenya and Mozambique shows that this is often uneven, as lack of clarity in laws and programmes contributes to school staff not having access to necessary tools (UNESCO, UNGEI and UNICEF, 2019).

Right to Play, a school-based programme in Hyderabad, Pakistan, using sports and games to empower students to reduce violence in school and change gender norms, decreased peer victimisation by 33% among boys and 59% among girls

Changes in curricula can prevent and address school-related gender-based violence, challenging gender norms to help create a non-violent culture. These changes can encourage students to reflect on their own gender biases and roles in society and help them understand different gender identities. Connect with Respect, a programme in the Kingdom of Eswatini, Thailand, Timor-Leste, the United Republic of Tanzania, Viet Nam, Zambia and Zimbabwe, supports students in challenging harmful practices through practical learning activities involving critical thinking, reflections among small groups and role playing (UNESCO, UNGEI and UNICEF, 2019). The Lights4Violence project, developed in 2017 by a cluster of universities in Italy, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Spain and the United Kingdom, aims to prevent gender-based violence among adolescents by developing communication, anger management, and non-violent conflict resolution skills (Vives-Cases et al., 2019).

Measures can fit into existing curricula and be used in the classroom or in extracurricular activities. A Right to Play, a school-based programme in Hyderabad, Pakistan, uses sports and games to empower students to reduce violence in school and change gender norms. As of 2018, the programme had reached 8,000 children in 40 public schools and resulted in decreases in peer victimization by 33% among boys and 59% among girls. Symptoms of depression fell by 10% among girls and 7% among boys (Heslop et al., 2017).

Access to comprehensive sexuality education is key to preventing school-related gender-based violence. Comprehensive sexuality education promotes gender-equal attitudes among students, including understanding and respect of other gender identities; improves life skills, teaching students to negotiate the terms of sexual activity, understand the importance of consent and resist peer pressure to engage in or accept violence; transforms teachers’ and parents’ attitudes by engaging them in school interventions; and improves reporting of and response to incidents of violence by providing information and explaining the importance of coordinating with other organizations and services (Plan International UK and SDDirect, 2015). Program H, for example, is an intervention developed by Brazilian-based NGO Promundo, which engages young men in changing inequitable and violent norms related to masculinity through critical reflection and dialogue about gender equality in participatory meetings. Since 2002, the programme has been implemented in 9 countries, while 26 countries have carried out training, activities or partial adaptations. Evaluations in eight African, Asian, Latin American and south-eastern European countries indicate positive changes in attitudes on gender equality and in self-reported behaviour such as couples communication, violence, condom use and caregiving (Promundo et al., 2013).

Violence can become normalized and accepted as part of school life by students and authorities, which results in it being under-reported and unpunished. Students fear victimization, punishment or ridicule, and teachers may discourage complaints to protect colleagues (UNGEI et al., 2018). Confidential, independent and easily accessible reporting mechanisms can provide victims and witnesses with secure channels to report incidents of gender-based violence. These mechanisms can include school-based focal points, suggestion boxes, telephone helplines, confidential counselling and online reporting methods, linked to strong referral and support systems (UNESCO, UNGEI and UNICEF, 2019).

Students, parents, communities and teacher unions should be involved in training that helps them to reflect critically on their attitudes and values towards gender equality

Measures can fit into existing curricula and be used in the classroom or in extracurricular activities. A Right to Play, a school-based programme in Hyderabad, Pakistan, uses sports and games to empower students to reduce violence in school and change gender norms. As of 2018, the programme had reached 8,000 children in 40 public schools and resulted in decreases in peer victimization by 33% among boys and 59% among girls. Symptoms of depression fell by 10% among girls and 7% among boys (Heslop et al., 2017).

Access to comprehensive sexuality education is key to preventing school-related gender-based violence. Comprehensive sexuality education promotes gender-equal attitudes among students, including understanding and respect of other gender identities; improves life skills, teaching students to negotiate the terms of sexual activity, understand the importance of consent and resist peer pressure to engage in or accept violence; transforms teachers’ and parents’ attitudes by engaging them in school interventions; and improves reporting of and response to incidents of violence by providing information and explaining the importance of coordinating with other organizations and services (Plan International UK and SDDirect, 2015). Program H, for example, is an intervention developed by Brazilian-based NGO Promundo, which engages young men in changing inequitable and violent norms related to masculinity through critical reflection and dialogue about gender equality in participatory meetings. Since 2002, the programme has been implemented in 9 countries, while 26 countries have carried out training, activities or partial adaptations. Evaluations in eight African, Asian, Latin American and south-eastern European countries indicate positive changes in attitudes on gender equality and in self-reported behaviour such as couples communication, violence, condom use and caregiving (Promundo et al., 2013).

Violence can become normalized and accepted as part of school life by students and authorities, which results in it being under-reported and unpunished. Students fear victimization, punishment or ridicule, and teachers may discourage complaints to protect colleagues (UNGEI et al., 2018). Confidential, independent and easily accessible reporting mechanisms can provide victims and witnesses with secure channels to report incidents of gender-based violence. These mechanisms can include school-based focal points, suggestion boxes, telephone helplines, confidential counselling and online reporting methods, linked to strong referral and support systems (UNESCO, UNGEI and UNICEF, 2019).

The Zero Tolerance Programme in Nepal incorporated a suggestion box as a reporting mechanism to encourage students to inform authorities of any incident. Students felt more comfortable sharing their concerns and suggestions, and teachers changed their mindsets and attitudes towards students and teaching practices (USAID, 2018). In 2013, Peru implemented the programme Si se ve (Yes I can see), which included an online platform and a helpline to encourage reporting of violence in school. Thanks to this tool, schools can avoid hiring teachers who have been sanctioned for having perpetrated any type of violence. In 2013–2018, the programme responded to more than 26,000 cases of violence reported from the 53,000 participating schools (Peru Ministry of Education, 2019). An innovative approach in Pikine, Senegal facilitated reporting and connected child victims with protective services. More than 700 volunteers were trained and organized into a network connected to social welfare services. The programme increased the reported number of child protection cases and established a real-time monitoring system via an online dashboard (UNICEF, 2018b).

Programmes should also teach young people to intervene when violence occurs. Bystander approaches involve teaching life skills to enable people to identify, report or involve others in responding to incidents of violence. In Hong Kong, China, the project Positive Adolescent Training through Holistic Social Programmes focused on teaching secondary school students to become helpful social bystanders. It provided awareness-raising activities on bullying, space for self-reflection and opportunities to practice new behaviour. A gender perspective in the design was considered essential, as boys are more likely to drop out of such programmes in societies where masculine role models are prevalent (Tsang, Hui and Law, 2011).

School staff sometimes reproduce prevailing gender norms in classrooms. Therefore, it is important to train teachers to reflect critically on their attitudes and values related to gender equality and to develop empathy towards students. Students, parents, communities and teacher unions should be involved in this training. The Education Unions Take Action to End School-related Gender-based Violence programme, implemented in Ethiopia, the Gambia, Kenya, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Uganda and Zambia, aims to empower teachers to become active agents to end violence in schools. Between 2016 and 2018, over 30,000 participants were reached through awareness-raising workshops in schools and union meetings (UNGEI et al., 2018).

Codes of conduct are being developed. In Sierra Leone, the government and the teachers’ union developed a code of conduct by holding multi-stakeholder consultations in all regions, which legitimized the code as a tool to support teacher professionalism (UNESCO and UN Women, 2016). South Africa’s teacher code of conduct was revised to identify ways to deal with perpetrators of violence (UNGEI et al., 2018). In Zambia, the Ministry of General Education launched teacher standards of practice in 2019. Standard 1.5 expects teachers to promote a safe and inclusive school environment, free from school-related gender-based violence, and to be able to prevent, identify and respond to incidents of violence in schools (Zambia Ministry of General Education and UNESCO, 2019).

Modifying or adapting school settings could prevent school violence and improve student safety. Shifting Boundaries is a programme created in 2010 in response to high levels of teen dating violence in schools in the United States that increases staff presence in spots where violence is likely to occur, as previously identified by students and teachers. An evaluation in New York found that the programme helped reduce sexual violence victimisation in dating relations by 50%, sexual violence perpetration by peers by 47% and sexual harassment by 34% (Holditch Niolon et al., 2017).

Progress in recognizing and responding to school-related gender-based violence in recent years has helped in developing a broader understanding of violence in schools. It is important to pay closer attention to girl-on-girl and girl-on-boy violence and to reconsider the female-victim/male-villain dichotomy. Further research is also needed on school violence directed at lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex students and on interventions that address it. Monitoring and evaluation mechanisms need to be strengthened if understanding of programme effectiveness is to improve. When education systems and schools make a concerted effort to address gender-based violence, they contribute to broader societal efforts to eliminate such violence and promote equality and respect. Schools should be a place where students feel safe and welcome, which is not possible if they remain sites of violence and gender inequality (Ginestra, 2020b).