Plan International Australia

Introduction

FIGURE 1: The one thing we all have in common is our differences

INCLUSION IN EDUCATION IS FIRST AND FOREMOST A PROCESS

Inclusion is for all. Inclusive education is commonly associated with the needs of people with disabilities and the relationship between special and mainstream education. Since 1990, the struggle of people with disabilities has shaped the global perspective on inclusion in education, leading to recognition of the right to inclusive education in Article 24 of the 2006 UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). However, as General Comment No. 4 on the article recognized in 2016, inclusion is broader in scope. The same mechanisms exclude not only people with disabilities but also others on account of gender, age, location, poverty, disability, ethnicity, indigeneity, language, religion, migration or displacement status, sexual orientation or gender identity expression, incarceration, beliefs and attitudes. It is the system and context that do not take diversity and multiplicity of needs into account, as the Covid-19 pandemic has also laid bare. It is society and culture that determine rules, define normality and perceive difference as deviance. The concept of barriers to participation and learning should replace the concept of special needs.

Inclusion is a process. Inclusive education is a process contributing to achievement of the goal of social inclusion. Defining equitable education requires a distinction between ‘equality’ and ‘equity’. Equality is a state of affairs (what): a result that can be observed in inputs, outputs or outcomes. Equity is a process (how): actions aimed at ensuring equality. Defining inclusive education is more complicated because process and result are conflated. This Report argues for thinking of inclusion as a process: actions that embrace diversity and build a sense of belonging, rooted in the belief that every person has value and potential, and should be respected, regardless of their background, ability or identity. Yet inclusion is also a state of affairs, a result, which the CRPD and General Comment No. 4 stopped short of defining with precision, likely because of differing views of what the result should be.

INCLUSION IN EDUCATION AS RESULT: START WITH EDUCATION FOR ALL

Poverty and inequality are major constraints. Despite progress in reducing extreme poverty, especially in Asia, it affects 1 in 10 adults and 2 in 10 children – 5 in 10 in sub-Saharan Africa. Income inequality is growing in parts of the world or, if falling, remains unacceptably high among and within countries. Key human development outcomes are also unequally distributed. In 30 low- and middle-income countries, 41% of children under age 5 from the poorest 20% of households were malnourished, more than twice the rate of those from the richest 20%, severely compromising their opportunity to benefit from education.

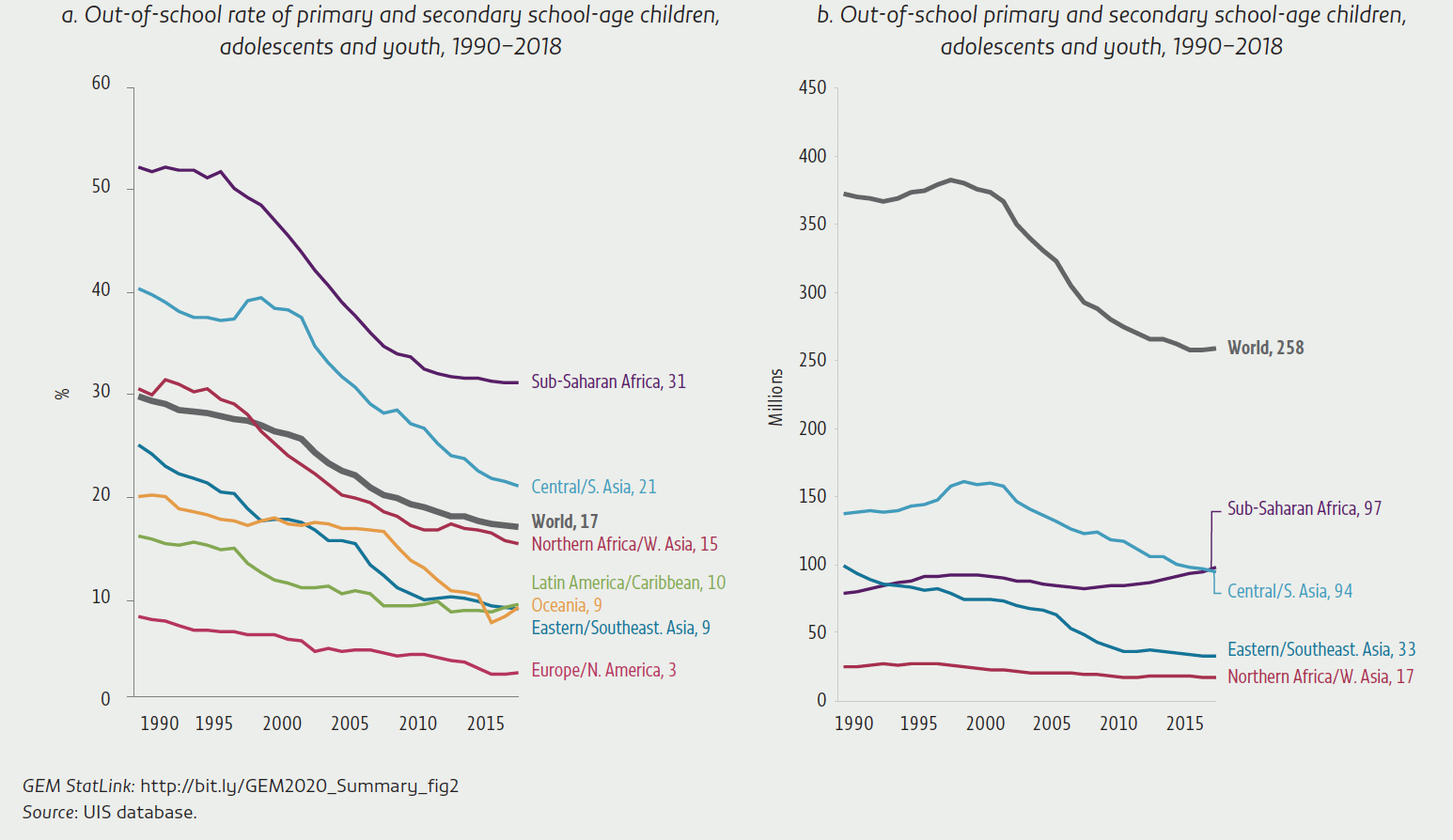

Progress in education participation is stagnating. An estimated 258 million children, adolescents and youth, or 17% of the total, are not in school (Figure 2). Disparities by wealth in attendance rates are large: Among 65 low-and middle-income countries, the average gap in attendance rates between the poorest and the richest 20% of households was 9 percentage points for primary school-age children, 13 for lower secondary school-age adolescents and 27 for upper secondary school-age youth. As the poorest are more likely to repeat and leave school early, wealth gaps are even higher in completion rates: 30 percentage points for primary, 45 for lower secondary and 40 for upper secondary school completion.

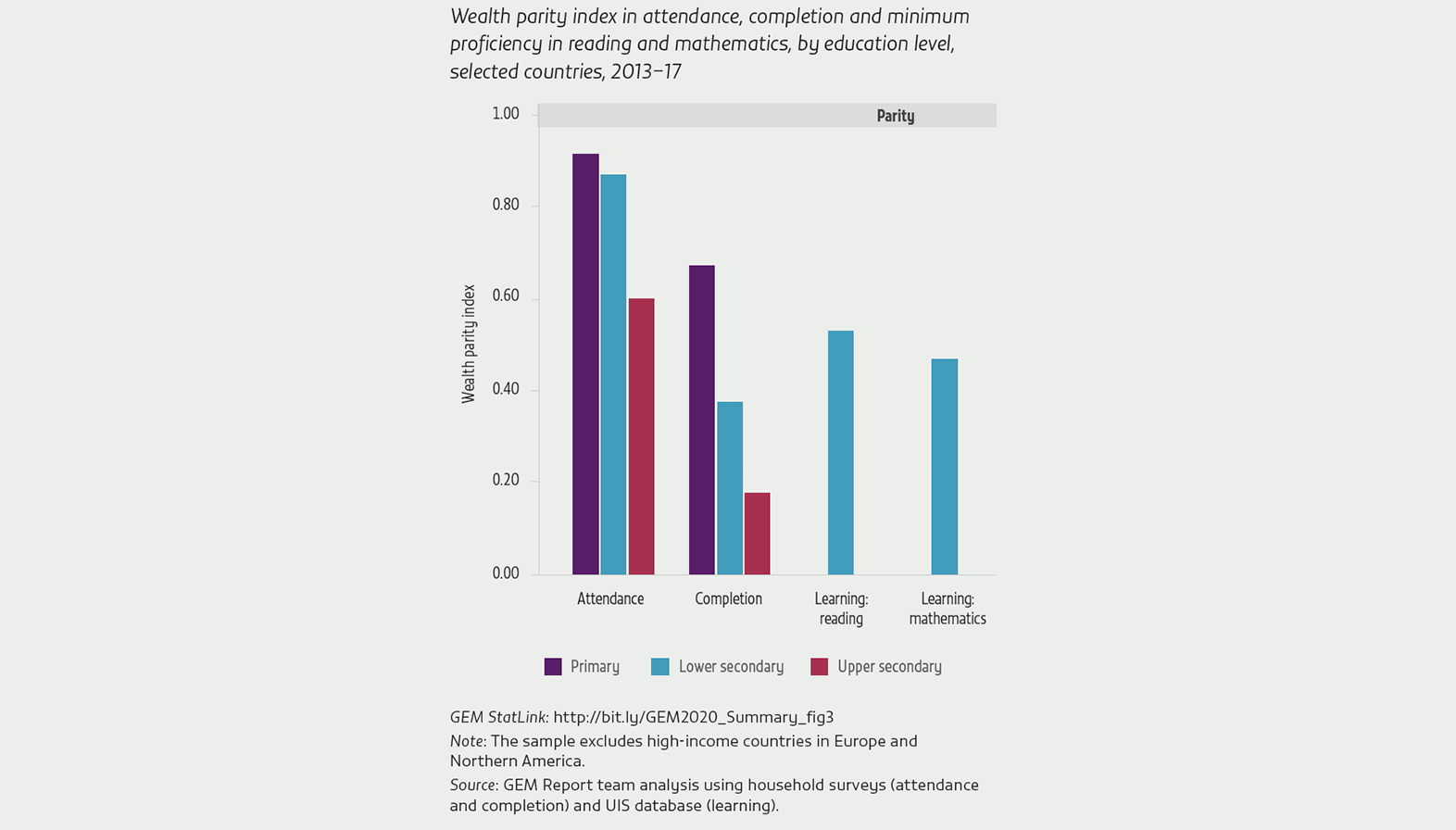

Poverty affects attendance, completion and learning opportunities. In all regions except Europe and Northern America, for every 100 adolescents from the richest 20% of households, 87 from the poorest 20% attended lower secondary school and 37 completed it. Of the latter, for every 100 adolescents from the richest 20% of households, about 50 achieved minimum proficiency in reading and mathematics (Figure 3). Often, disadvantages intersect. Those most likely to be excluded from education are also disadvantaged due to language, location, gender and ethnicity. In at least 20 countries with data, hardly any poor rural young woman completed upper secondary school.

FIGURE 2: A quarter of a billion children, adolescents and youth are not in school

FIGURE 3: There are large wealth disparities in attendance, completion and learning

THE RESULTS OF INCLUSION IN EDUCATION MAY BE ELUSIVE, BUT ARE REAL, NOT ILLUSIVE

While universal access to education is a prerequisite for inclusion, there is less consensus on what else it means to achieve inclusion in education for learners with disabilities and other disadvantaged groups at risk of exclusion.

Inclusion for students with disabilities means more than placement. The CRPD focus on school placement marked a break not just with the historical tendency to exclude children with disabilities from education or to segregate them in special schools but also with the practice of putting them in separate classes for much or most of the time. Inclusion, however, involves many more changes in school support and ethos. The CRPD did not argue special schools violated the convention, but recent reports by the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities increasingly point in that direction. The CRPD gave governments a free hand in the form of inclusive education, implicitly recognizing the obstacles to full inclusion. While exclusionary practices by many governments that contravene their CRPD commitments should be exposed, the limits to how flexible mainstream schools and education systems can be should also be acknowledged.

Inclusive education serves multiple objectives. There is a potential tension between the desirable goals of maximizing interaction with others (all children under the same roof and fulfilling learning potential (wherever students learn best. Other considerations include the speed with which systems can move towards the ideal and what happens during transition, and the trade-off between early needs identification and the risk of labelling and stigmatization.

Pursuing different objectives simultaneously can be complementary or conflicting. Policymakers, legislators and educators confront delicate and context-specific questions related to inclusion. They need to be aware of opposition by those invested in preserving segregated delivery but also of the potential unsustainability of rapid change, which can harm the welfare of those it is meant to serve. Including children with disabilities in mainstream schools that are not prepared, supported or accountable for achieving inclusion can intensify experiences of exclusion and provoke backlash against making schools and systems more inclusive.

There can be downsides to full inclusion. In some contexts, inclusion may inadvertently intensify pressure to conform. Group identities, practices, languages and beliefs may be devalued, jeopardized or eradicated, undercutting a sense of belonging. The right for a group to preserve its culture and the right to self-determination and self-representation are increasingly recognized. Inclusion may be resisted out of prejudice but also out of recognition that identity may be maintained and empowerment achieved only if a minority is a majority in a given area. Rather than achieve positive social engagement, in some circumstances inclusion policies may exacerbate social exclusion. Exposure to the majority may reinforce dominant prejudices, intensifying minority disadvantage. Targeting assistance can also lead to stigmatization, labelling or unwelcome forms of inclusion.

Resolving dilemmas requires meaningful participation. Inclusive education should be based on dialogue, participation and openness. While policymakers and educators should not compromise, discount or divert from the long-term ideal of inclusion, they should not override the needs and preferences of those affected. Fundamental human rights and principles provide moral and political direction for education decisions, yet fulfilling the inclusive ideal is not trivial. Delivering sufficient differentiated and individualized support requires perseverance, resilience and a long-term perspective. Moving away from education system design that suits some children and obliges others to adapt cannot easily happen by decree. Prevailing attitudes and mindsets must be challenged. Inclusive education may prove intractable, even with the best will and highest commitment. Some, therefore, argue for limiting the ambition of inclusive education, but the only way forward is to acknowledge the barriers and dismantle them.

Inclusion brings benefits. Careful planning and provision of inclusive education can deliver improvement in academic achievement, social and emotional development, self-esteem and peer acceptance. Including diverse students in mainstream classrooms and schools can prevent stigma, stereotyping, discrimination and alienation. There are also potential efficiency savings from eliminating parallel education structures and using resources more effectively in a single inclusive mainstream system. However, economic justification for inclusive education, while valuable for planning, is not sufficient. Few systems come close enough to the ideal to allow estimation of the full cost, and benefits are hard to quantify, as they extend over generations.

Inclusion is a moral imperative. Debating the benefits of inclusive education is akin to debating the benefits of human rights. Inclusion is a prerequisite for sustainable societies. It is a prerequisite for education in, and for, a democracy based on fairness, justice and equity. It provides a systematic framework for removing barriers according to the principle ‘every learner matters and matters equally’. It also counteracts education system tendencies that allow exceptions and exclusions, as when schools are evaluated along a single dimension and resource allocation is linked to their performance.

Inclusion improves learning for all students. In recent years, a learning crisis narrative has drawn attention to the majority of school-age children in low- and middle-income countries not achieving minimum proficiency in basic skills. However, this narrative may overlook dysfunctional features of education systems in the countries furthest behind, such as exclusion, elitism and inequity. It is not by accident that SDG 4 explicitly exhorts countries to ensure inclusive education. Mechanical solutions that do not address the deeper barriers of exclusion can only go so far towards improving learning outcomes. Inclusion must be the foundation of approaches to teaching and learning.

Laws and policies

Binding legal instruments and non-binding declarations express international aspirations for inclusion. The 1960 UNESCO Convention against Discrimination in Education and the 1990 World Declaration on Education for All, adopted in Jomtien, Thailand, called on countries to take measures to ensure ‘equality of treatment in education’ and no ‘discrimination in access to learning opportunities’ for ‘underserved groups’. The 1994 Statement and Framework for Action adopted in Salamanca, Spain, put forward the principle that all children should be at ‘the school that would be attended if the child did not have a disability’, which was endorsed as a right in 2006. These texts have influenced the national laws and policies on which progress towards inclusion hinges.

National definitions of inclusive education tend to embrace a broader scope. Analysis for this Report shows that 68% of countries define inclusive education in laws, policies, plans or strategies. Definitions that cover all marginalized groups are found in 57% of countries. In 17% of countries, the definition of inclusive education covers exclusively people with disabilities or special needs. (PEER).

Laws tend to target specific groups at risk of exclusion in education. The broad vision of including all learners in education is largely absent from national laws. Only 10% of countries reflected comprehensive provisions for all learners in their general or inclusive education laws. More commonly, legislation originating in education ministries concerns specific groups. Of all countries, 79% had laws referring to education for people with disabilities, 60% for linguistic minorities, 50% for gender equality and 49% for ethnic and indigenous groups. (PEER).

Policies tend to have a broader vision of inclusion in education. About 17% of countries have policies containing comprehensive provisions for all learners. The tendency is much stronger in less binding texts, with 75% of national education plans and strategies declaring an intention to include all disadvantaged groups. Some 67% of countries have policies on inclusion of learners with disabilities, with responsibility for these policies almost equally split between education ministries and other ministries. (PEER)

Laws and policies differ on whether students with disabilities should be in mainstream schools. Laws in 25% of countries provide for education in separate settings, with shares exceeding 40% in Asia and in Latin America and the Caribbean. About 10% of countries mandate integration and 17% inclusion, the remainder opting for combinations of segregation and mainstreaming. Policies have shifted closer to inclusion: 5% of countries have policy provisions for education in separate settings, while 12% opt for integration and 38% for inclusion. Despite the good intentions enshrined in laws and policies, governments often do not ensure implementation.

Policies need to be consistent and coherent across ages and education levels. Access to early childhood care and education is highly inequitable, conditioned by location and socio-economic status. Quality, especially interactions, integration, and child-centredness based on play, also determines inclusion. Early identification of children’s needs is crucial to designing the right responses, but labels of difference in the name of inclusion can misfire. Disproportionately assigning some marginalized groups to special needs categories can indicate discriminatory procedures, as successful legal challenges over Roma students’ right to education demonstrate.

Preventing early school leaving requires policies on multiple fronts. Education systems face a dilemma. Grade retention appears to increase dropout, but automatic promotion requires systematic approaches to remedial support, which many countries proclaim but fail to implement. Laws and policies may not be consistent with inclusion, e.g. in countries with low child labour or marriage age thresholds. Bangladesh is among the few countries to invest extensively in second-chance programmes, which are indispensable for achieving SDG 4.

Governments are striving to make post-compulsory and adult education policies more inclusive. Technical and vocational education can facilitate labour market inclusion of vulnerable groups, notably young women and people with disabilities. Unlocking its potential requires making learning environments safer and accessible, as in Malawi. Inclusion-oriented tertiary education interventions tend to focus on encouraging access for disadvantaged groups through quotas or affordability measures. Yet only 11% of 71 countries had comprehensive equity strategies; another 11% elaborated approaches only for particular groups. Digital inclusion, especially of the elderly, is a major challenge for countries increasingly dependent on information and communication technology (ICT).

Responses to the Covid-19 crisis, which affected 1.6 billion learners, have not paid sufficient attention to including all learners. While 55% of low-income countries opted for online distance learning in primary and secondary education, only 12% of households in least developed countries have internet access at home. Even low-technology approaches cannot ensure learning continuity. Among the poorest 20% of households, just 7% owned a radio in Ethiopia and none owned a television. Overall, about 40% of low- and lower-middle-income countries have not supported learners at risk of exclusion. In France, up to 8% of students had lost contact with teachers after three weeks of lockdown.

Data

Data on and for inclusion in education are essential. Data on inclusion can highlight gaps in education opportunities and outcomes among learner groups, identifying those at risk of being left behind and the severity of the barriers they face. Using such information, governments can develop policies for inclusion and collect further data on implementation and on less easily observed qualitative outcomes.

Formulating appropriate questions on characteristics associated with vulnerability can be sensitive. Data on education disparity at the population level, collected through censuses and surveys, raise education ministries’ awareness of disparity. However, depending on their formulation, questions on characteristics such as nationality, ethnicity, religion, sexual orientation and gender identity expression can touch on sensitive personal identities, be intrusive and trigger persecution fears.

The formulation of questions on disability has improved. Agreeing to a valid measure of disability has been a long process. The UN Statistical Commission’s Washington Group on Disability Statistics proposed a short set of questions for censuses or surveys in 2006, covering critical functional domains and activities for adults. A child-specific module was then developed with UNICEF. The questions bring disability statistics in line with the social model of disability and resolve serious comparability issues. Their rate of adoption is only slowly picking up.

The evidence that emerges on disability is of higher quality but still patchy. Analysis of 14 countries taking part in the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) in 2017–19 and using the wider child-specific module showed a disability prevalence of 12%, ranging from 6% to 24%, as a result of high anxiety and depression rates. Across these countries, children, adolescents and youth with disabilities accounted for 15% of the out-of-school population. Relative to their peers of primary, lower secondary and upper secondary school age, those with a disability were more likely to be out of school by 1, 4 and 6 percentage points, respectively, and those with a sensory, physical or intellectual disability by 4, 7 and 11 percentage points.

Some school surveys provide deeper insights into inclusion. In the 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), one in five 15-year-old students reported feeling like an outsider at school, but the share exceeded 30% in Brunei Darussalam, the Dominican Republic and the United States. In all participating education systems, students of lower socio-economic status were less likely to feel a sense of belonging. Administrative data can be leveraged to collect qualitative evidence on inclusion. New Zealand systematically monitors soft indicators at the national level, including on whether students feel cared for, safe and secure, and on their ability to establish and maintain positive relationships, respect others’ needs and show empathy. Almost half of low- and middle-income countries collect no administrative data on students with disabilities.

Data show where segregation is still taking place. In Brazil, a policy change increased the share of students with disabilities in mainstream schools from 23% in 2003 to 81% in 2015. In Asia and the Pacific, almost 80% of children with disabilities attended mainstream schools, from 3% in Kyrgyzstan to 100% in Timor-Leste and Thailand. Scattered data record schools catering to specific groups, such as girls, linguistic minorities and religious communities. Their contribution to inclusion is ambiguous: Indigenous schools, for instance, can provide an environment where traditions, cultures and experiences are respected, but they can also perpetuate marginality. School surveys such as PISA show high levels of socio-economic segregation in countries including Chile and Mexico, where half of all students would require school reassignment to achieve a uniform socio-economic mix. This type of school segregation barely changed over 2000–15.

Identification of special education needs can be contentious. Identification can inform teachers about student needs so they can target support and accommodation. Yet children could be reduced to labels by peers, teachers and administrators, which can prompt stereotyped behaviours towards labelled students and encourage a medical approach. Portugal recently legislated a non-categorical approach to determining special needs. Low expectations triggered by a label, such as having learning difficulties, can become self-fulfilling. In Europe, the share of students identified with special education needs ranged from 1% in Sweden to 20% in Scotland. Learning disability was the largest category of special needs in the United States but was unknown in Japan. Such variation is mainly explained by differences in how countries construct this category of education: Institution, funding and training requirements vary, as do policy implications.

Governance and finance

Ensuring inclusive education is not the sole responsibility of education policy actors. Integrating services can improve the way children’s needs are considered, as well as services’ quality and cost-effectiveness. Integration can be achieved when one service provider acts as a referral point for access to another. A mapping of inclusive education provision in 18 European countries, mostly with reference to students with disabilities, showed education ministries responsible for teachers, school administration and learning materials; health ministries for screening, assessment and rehabilitation services; and social protection ministries for financial aid.

Sharing responsibility does not guarantee horizontal collaboration, cooperation and coordination. Deep-rooted norms, traditions and bureaucratic working cultures hinder smooth transition away from siloed forms of service delivery. Insufficient resources may also be a factor: In Kenya, one-third of county-level Educational Assessment Resource Centres, set up to expand access to education for children with disabilities, had one officer instead of the multidisciplinary teams envisaged. Clearly defined, measurable standards outlining responsibilities are needed. Rwanda developed standards enabling inspectors to assess classroom inclusivity. In Jordan, various actors used separate standards for licensing and accrediting special education centres; the new 10-year strategy will address this issue.

Vertical integration among government tiers and support to local government are needed. Central governments must fund commitments to local governments fully and develop their capacity. A Republic of Moldova reform to move children out of mostly state boarding schools stumbled because savings were not transferred to the local government institutions and schools absorbing the children. In Nepal, a midterm evaluation of the school sector programme and the first inclusive education workshop showed that, while some central government posts were shifted as part of decentralization, local government capacity to support education service delivery was weak.

Three funding levers are important for equity and inclusion in education. First, governments may or may not compensate for relative disadvantage in allocating resources to local authorities or schools through capitation grants. Argentina’s federal government allocates block grants to provincial governments, taking rural and out-of-school populations into account. Provinces co-finance education from their revenue, whose levels vary greatly, contributing to inequality. Second, education financing policies and programmes may target students and their families in the form of cash (e.g. scholarships) and exemptions from payment (e.g. fees). About one in four countries have affirmative action programmes for access to tertiary education. Third, non-education-specific financing policies and programmes can have a large impact on education. Over the long term, conditional cash transfers in Latin America increased education attainment by between 0.5 and 1.5 years.

Financing disability-inclusive education requires additional focus. A twin-track approach to financing is recommended, complementing general mechanisms with targeted programmes. Policymakers need to define standards for services to be delivered and the costs they will cover. They need to address the challenge of expanding costs as special needs identification rates increase, and design ways to prioritize, finance and deliver targeted services for a wide range of needs. They also need to define results in a way that maintains pressure on local authorities and schools to avoid further earmarking services for children with diagnosed special needs and further segregating settings at the expense of other groups or general financing needs. Finland has been moving in this direction.

Even richer countries lack information on financing education for students with disabilities. A project mapping European countries’ financing of inclusive education found that only 5 in 18 had relevant information. There is no ideal funding mechanism, since countries vary in history, understanding of inclusive education and levels of decentralization. A few countries are moving away from multiple weights (e.g. by type of impairment), which may inflate the number of students identified with special needs, to a simple funding formula for mainstream schools. Many promote networks to share resources, facilities and capacity development opportunities.

Poorer countries often struggle to finance the shift from special to inclusive education. Some countries have increased their budgets to improve inclusion of students with disabilities. The 2018/19 Mauritius budget quadrupled the annual per capita grant for teaching aids, utilities, furniture and equipment for students with special needs.

Curricula, textbooks and assessments

Curriculum choices can promote or obstruct an inclusive and democratic society. Curricula need to reassure all groups at risk of exclusion that they are fundamental to the education project, whether in terms of content or implementation. Using different curricula of differing standards for some groups hinders inclusion and creates stigma. Yet many countries still teach students with disabilities a special curriculum, offer refugees only the curriculum of their home country to encourage repatriation, and tend to push lower achievers onto slower education tracks. Challenges arise in several contexts: internally displaced populations in Bosnia and Herzegovina; gender issues in Peru; linguistic minorities in Thailand; Burundian and Congolese refugees in the United Republic of Tanzania; indigenous peoples in Canada. In Europe, 23 in 49 countries did not address sexual orientation and gender identity expression explicitly.

Inclusive curricula need to be relevant, flexible and responsive to needs. Evidence from citizen-led assessments in Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa highlighted large gaps between curriculum objectives and learning outcomes. When curricula cater to more privileged students and certain types of knowledge, implementation inequality between rural and urban areas arises, as a curriculum study of primary mathematics in Uganda showed. Learning in the mother tongue is vital, especially in primary school, to avoid knowledge gaps and increase the speed of learning and comprehension. In India’s Odisha state, multilingual education covered about 1,500 primary schools and 21 tribal languages of instruction. Just 41 countries worldwide recognize sign language as an official language, of which 21 are in the European Union. In Australia, 19% of students receive adjustments to the curriculum. Curricula should not lead to dead ends in education but offer pathways for continuous education opportunities.

Textbooks can perpetuate stereotypes. Representation of ethnic, linguistic, religious and indigenous minorities in textbooks depends largely on historical and national context. Factors influencing countries’ treatment of minorities include the presence of indigenous populations; the demographic, political or economic dominance of one or more ethnic groups; the history of segregation or conflict; the conceptualization of nationhood; and the role of immigration. Textbooks may acknowledge minority groups in ways that mitigate or exacerbate the degree to which they are perceived, or perceive themselves, as ‘other’. Inappropriate images and descriptions that associate certain characteristics with particular population groups can make students with non-dominant backgrounds feel misrepresented, misunderstood, frustrated and alienated. In many countries, females are often under-represented and stereotyped. The share of females in secondary school English language textbook text and images was 44% in Indonesia, 37% in Bangladesh and 24% in Punjab province, Pakistan. Women were represented in less prestigious occupations and as introverted.

Good-quality assessments are a fundamental part of an inclusive education system. Assessments are often organized unduly narrowly, determining admission to certain schools or placement in separate school tracks, and sending conflicting signals about government commitment to inclusion. Large-scale, cross-national summative assessments, for instance, tend to exclude students with disabilities or learning difficulties. Assessment should focus on students’ tasks: how they tackle them, which ones prove difficult and how some aspects can be adapted to enable success. A shift in emphasis from high-stake summative assessments at the end of the education cycle to low-stake formative assessments over the education trajectory underpins efforts to make assessment fit for the purpose of inclusive education. Test accommodations are essential, but their validity has been questioned in that they appear to fit students to a model. The emphasis should instead be on how the assessment can support students with impairments in demonstration of their learning. In seven sub-Saharan African countries, no teacher had minimum knowledge in student assessment.

Various factors need to be aligned for inclusive curricular, textbook and assessment reforms. Capacity needs to be developed so stakeholders can work collaboratively and think strategically. Partnerships need to be in place to enable all parties to own the process and work towards the same goals. Successful attempts to make curricula, textbooks and assessments inclusive entail participatory processes during design, development and implementation.

Teachers and education support personnel

In inclusive education, all teachers should be prepared to teach all students. Inclusion cannot be realized unless teachers are agents of change, with values, knowledge and attitudes that permit every student to succeed. Teachers’ attitudes often mix commitment to the principle of inclusion with doubts about their preparedness and how ready the education system is to support them. Teachers may not be immune to social biases and stereotypes. Inclusive teaching requires teachers to be open to diversity and aware that all students learn by connecting classroom with life experiences. While many teacher education and professional learning opportunities are designed accordingly, entrenched views of some students as deficient, unable to learn or incapable mean teachers may struggle to see that each student’s learning capacity is open-ended.

Lack of preparedness for inclusive teaching may result from gaps in pedagogical knowledge. Some 25% of teachers in the 2018 Teaching and Learning International Survey reported a high need for professional development in teaching students with special needs. Across 10 francophone sub-Saharan African countries, 8% of grade 2 and 6 teachers had received in-service training in inclusive education. Overcoming the legacy of preparing different types of teachers for different types of students in separate settings is important. To be of good quality, teacher education must cover multiple aspects of inclusive teaching for all learners, from instructional techniques and classroom management to multi-professional teams and learning assessment methods, and should include follow-up support to help teachers integrate new skills into classroom practice. In Canada’s New Brunswick province, a comprehensive inclusive education policy introduced training opportunities for teachers to support students with autism spectrum disorders.

Teachers need appropriate working conditions and support to adapt teaching to student needs. In Cambodia, teachers questioned the feasibility of applying child-centred pedagogy in a context of overcrowded classrooms, scarce teaching resources and overambitious curricula. Teaching to standardized content requirements of a learning assessment can make it more difficult for teachers to adapt their practice. Cooperation among teachers in different schools can support them in addressing the challenges of diversity, especially in systems transitioning from segregation to inclusion. Sometimes such collaboration is absent even among teachers at the same school. In Sri Lanka, few teachers in mainstream classes collaborated with peers in special needs units.

A rise in support personnel accompanied the mainstreaming of students with special needs. Yet, globally, provision is lacking. Respondents to a survey of teacher unions reported that support personnel were largely absent or not available in at least 15% of countries. Classroom learning or teaching assistants can be particularly helpful. However, while their role is to supplement teachers’ work, they are often put in positions that demand much more. Increased professional expectations, accompanied by often low levels of professional development, can lead to lower-quality learning, interference with peer interaction, decreased access to competent instruction, and stigmatization. In Australia, access of students with disabilities to qualified teachers was partly impeded by the system’s overdependence on unqualified support personnel.

Teacher diversity often lags behind population diversity. This is sometimes the result of structural problems preventing members of marginalized groups from acquiring qualifications, teaching in schools once they are qualified and remaining in the profession. Systems should recognize that these teachers can bolster inclusion by offering unique insights and serving as role models to all students. In India, the share of teachers from scheduled castes, which constitute 16% of the country’s population, increased from 9% to 13% between 2005 and 2013.

Schools

Inclusion in education requires inclusive schools. School ethos – the explicit and implicit values and beliefs, as well as the interpersonal relationships, that define a school’s atmosphere – has been linked to students’ social and emotional development and well-being. The share of students in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries who felt they ‘belonged’ in school fell from 82% in 2003 to 73% in 2015 due to increasing shares of students with immigrant backgrounds and declining levels of a sense of belonging among natives.

Head teachers can foster a shared vision of inclusion. They can guide inclusive pedagogy and plan professional development activities. A cross-country study of teachers of special needs students in mainstream schools found that those who received more instructional leadership reported lower professional development needs. While head teachers’ tasks are increasingly complex, nearly one-fifth (rising to half in Croatia) had no instructional leadership training. Across 47 education systems, 15% of head teachers (rising to more than 60% in Viet Nam) reported a high need for professional development in promoting equity and diversity.

School bullying and violence cause exclusion. One-third of 11- to 15-year-olds have been bullied in school. Those perceived as differing from social norms or ideals are the most likely to be victimized, including sexual, ethnic and religious minorities, the poor and those with special needs. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex students in New Zealand were three times as likely to be bullied. In Uganda, 84% of children with disabilities versus 53% of those without experienced violence by peers or staff. Classroom management practices, guidance services and policies should identify staff responsibilities and actions to prevent and address bullying and violence. Punitive approaches should not displace student support and cultivation of a respectful atmosphere.

Schools must be safe and accessible. Transit to school, building design and sanitation facilities often violate accessibility, acceptability and adaptability principles. More than one-quarter of girls in 11 African, Asian and Latin American countries reported never or seldom feeling safe on the way to or from school. No schools in Burundi, Niger and Samoa had ‘adapted infrastructure and materials for students with disabilities’. In Slovakia, 15% of primary and 21% of lower secondary schools met such standards. Reliable comparable evidence remains elusive because countries’ standards vary and schools do not meet all elements of a standard; in addition, monitoring capacity is weak and data are not independently verified.

Accessible infrastructure often does not support all. The CRPD called for universal design to increase functionality and accommodate everyone’s needs, regardless of age, size or ability. Incorporating full-access facilities from the outset increases cost by 1%, compared with 5% or more after completion. Aid programmes helped disseminate universal design principles. Indonesian schools built with Australian support included accessible toilets, handrails and ramps; the government adopted similar measures for all new schools.

Assistive technology can determine participation or marginalization. Assistive devices refer to input technology (adapted keyboards and computer input controls, speech input, dictation software) and output technology (screen readers and magnifiers, three-dimensional printers, Braille note-takers). Alternative and augmentative communication systems replace speech. Assistive listening systems improve sound clarity and reduce background noise. Such technology improves graduation rates, self-esteem and optimism, but is often unavailable due to lack of resources or not used effectively due to lack of teacher education.

Students, parents and communities

Take marginalized students’ experiences into account. Documenting disadvantaged students’ views without singling them out is difficult. Their inclusion preferences are shown to depend on their vulnerability, type of school attended, experience at a different type of school, and the level and discreetness of specialized support. Vulnerable students in mainstream schools may appreciate separate settings for the sake of increased attention or reduced noise. Pairing students with peers with disabilities can increase acceptance and empathy, although it does not guarantee inclusion outside school.

Majority populations tend to stereotype minority and marginalized students. Negative attitudes lead to less acceptance, isolation and bullying. Syrian refugees in Turkey felt negative stereotypes led to depression, stigmatization and alienation from school. Stereotypes can lower students’ expectations and self-esteem. In Switzerland, girls internalized the view that they are less suited than boys for science, technology, engineering and mathematics, which discouraged them from pursuing degrees in these fields. Teachers can fight but also perpetuate discrimination in education. Mathematics teachers in São Paulo, Brazil, were more likely to pass white students than their equally proficient and well-behaved black classmates. Teachers in China had less favourable perceptions of rural migrant students than of their urban peers.

Parents drive but also resist inclusive education. Parents may hold discriminatory beliefs about gender, disability, ethnicity, race or religion. Some 15% in Germany and 59% in Hong Kong, China, feared that children with disabilities disturbed others’ learning. Given choice, parents wish to send their vulnerable children to schools that ensure their well-being. They need to trust mainstream schools to respond to their needs. As school becomes more demanding with age, parents of children with autism spectrum disorders may have to look for schools that better meet their needs. In Australia’s Queensland state, 37% of students in special schools had moved from mainstream schools.

Parental school choice affects inclusion and segregation. Families with choice may avoid disadvantaged local schools. In Danish cities, a seven percentage point increase in the share of migrant students was associated with a one percentage point increase in the share of natives attending private school. In Lebanon, the majority of parents favoured private schools along sectarian lines. In Malaysia, private school streams organized by ethnicity and differentiated by quality contributed to stratification, despite government measures to desegregate schools. The potential of distance and online mainstream education for inclusion notwithstanding, parental preference for self-segregation through homeschooling tests the limits of inclusive education.

Parents of children with disabilities often find themselves in a distressing situation. Parents need support in early identification and management of their children’s sleep, behaviour, nursing, comfort and care. Early intervention programmes can help them grow confident, use other support services and enrol children in mainstream schools. Mutual support programmes can provide solidarity, confidence and information. Parents with disabilities are more likely to be poor, less educated and face barriers coming to school or working with teachers. In Viet Nam, children of parents with disabilities had 16% lower attendance rates.

Civil society has been advocate and watchdog for the right to inclusive education. Organizations for people with disabilities, disabled people’s organizations, grassroots parental associations and international non-government organizations (NGOs) active in development and education monitor progress on government commitments, campaign for fulfilment of rights and defend against violations of the right to inclusive education. In Armenia, an NGO campaign resulted in a legal and budget framework for rolling out inclusive education nationally by 2025.

Civil society groups provide education services on government contract or their own initiative. These services may support groups governments do not reach (e.g. street children) or be alternatives to government services. The Ghana Inclusive Education Policy calls on NGOs to mobilize resources, advocate for increased funding, contribute to infrastructure development and engage in monitoring and evaluation. The Afghanistan government supports community-based education, which relies on local people. Yet NGO schools set up for specific groups may promote segregation rather than inclusion in education. They should align with policy and not replicate services or compete for limited funds.