Credit: Malama Mwila / Save the Children44GENDER REPORT

In strategic objective B.1, the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action called on countries to make education systems gender-sensitive, take measures to increase the proportion of women participating in education policymaking and decision making, and boost the share of female teachers in all education levels and fields, including traditionally male-dominated STEM disciplines. Educators also need to be open to girls’ and boys’ choices and help them explore who they are, connect to people around them and gain self-confidence, well-being, peer acceptance and social support (Lahelma, 2011). School experiences should not undermine the message that students can do any work they want and become anything they want to be.

Gender norms and stereotypes are learned in early childhood. But few countries pay attention to gender equality in early childhood teaching and learning. In Australia and Norway and in Hong Kong, China, preschool teachers manifest traditional gender values in the classroom (Chi, 2018). A study of 6-year-olds in the United States showed they had stereotyped views about boys being better than girls at robots and programming. There was no gap in interest and self-efficacy in technology between Grade 1 boys and those girls who were offered programming experience (Master et al., 2017). The Forum for African Women Educationalists has promoted gender-responsive pedagogy in several countries, encouraging teachers to bring gender awareness to the classroom to enhance girls’ self-esteem. In Malawi, attention has focused on early years to overcome constraints created by lower societal expectations that negatively affect girls’ development before they reach adolescence (Banda, 2018).

Gender shapes teacher perceptions of student academic ability and behaviour (Bettie, 2002; Ispa-Landa, 2013; Cherng and Han, 2018). For instance, teachers are more likely to characterize boys’ behaviour as disruptive than girls’ (Jones and Myhill, 2004;Schaeffer et al., 2006). A study of 527 teachers in 27 primary schools in three Chinese provinces found that female teachers rated boys as more disruptive and inattentive in class than girls, while differences in male teacher ratings were smaller (Caldarella et. al 2009). Teacher attitudes can mirror societal biases. In Mexico, teachers’ negative attitudes about inclusion of Maya children, as well as prejudiced behaviour towards Mayan girls with darker skin tones, reduced the girls’ self-esteem and capacity to concentrate in class (Osorio Vázquez, 2017). A study on culturally diverse high schools in the United States showed that white teachers believed black boys more frequently talked in class, were late and broke the dress code; as a result, black boys systematically experienced racial insults and invalidation (Hotchkins, 2016).

The Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action called on countries to make education systems gender-sensitive and take measures to increase the proportion of women participating in education policymaking and decision making

Teacher attitudes affect student achievement, even when they are not explicit. In Italy, girls assigned to teachers with implicit gender bias underperformed in mathematics and chose less demanding secondary schools, following teachers’ recommendations (Carlana, 2019). Teacher attitudes also lead to increased disciplinary action and suspensions. In the United States in 2013/14, black boys were suspended 2.4 times as often as white boys and black girls 3 times as often as white girls (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019), suggesting that the intersection between gender and race is more significant for females than males (Crenshaw et al., 2015).

Teachers thus need to acquire knowledge and skills to address pressing inclusion issues such as gender equality. Chile’s 2015–2018 Education for Gender Equality Plan introduced ongoing teacher education at the national level on gender, discrimination, inclusive schooling, sexuality and sexual diversity in the classroom (Chile Ministry of Education, 2017). Cuba’s Sexuality Education Programme seeks to strengthen teacher education on sexuality as well as on preventing HIV and other sexually transmitted infections, using a gender and sexual rights approach throughout the basic curriculum, electives and post-graduate studies (Cuba Ministry of Education, 2011). In Nepal, the National Centre for Educational Development incorporated a gender awareness module in its teacher professional development programme (OHCHR, 2017). Uganda’s 2019 National Teacher Policy has developed and piloted guidelines to equip teachers with basic knowledge about gender concepts and skills for gender-responsive pedagogy in STEM (UNESCO, 2019c).

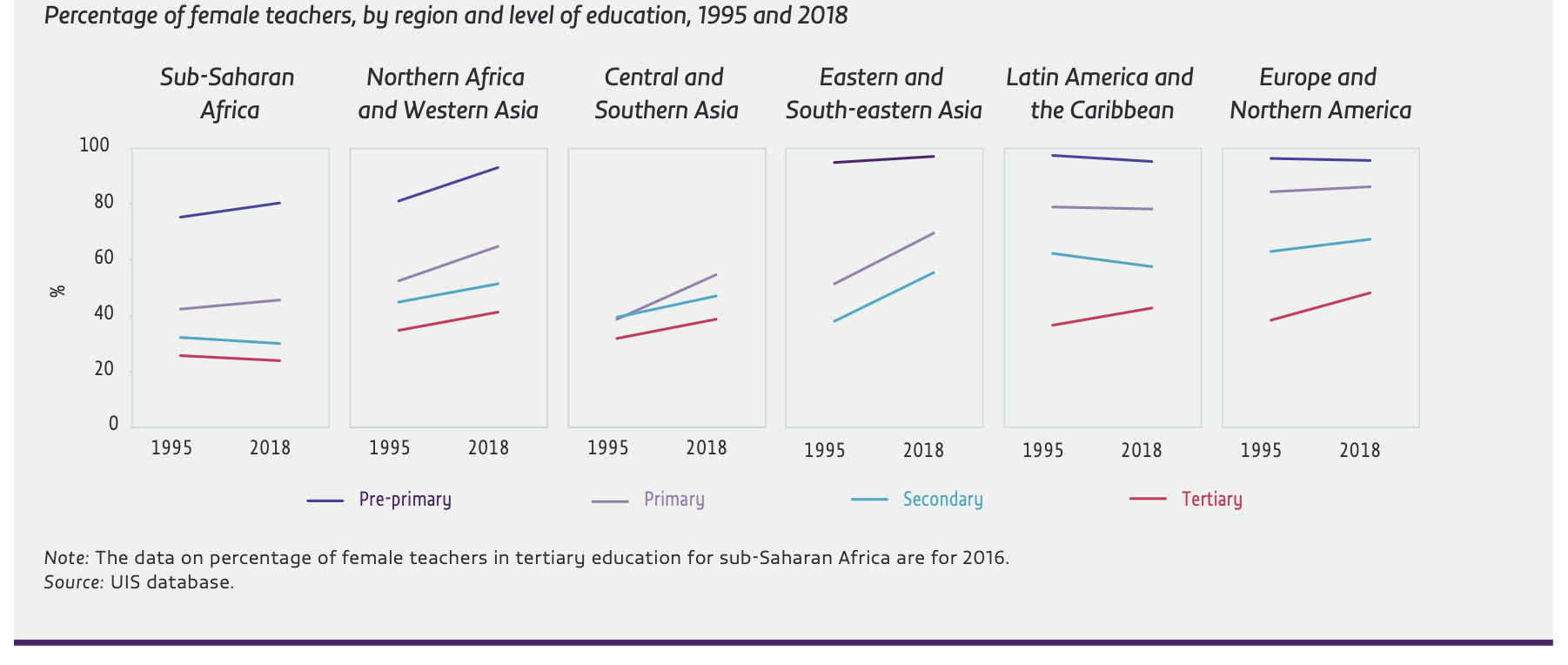

Globally, women represented 94% of teachers in pre-primary, 66% in primary, 54% in secondary and 43% in tertiary education in 2018

Whole-school approaches can be even more effective than those targeting only teachers. The Lifting Limits Programme was piloted in 2018/19 in five primary schools in London. Using a whole-school approach, it aimed to increase awareness and provide 270 staff and 1,900 students with tools to recognize and correct unintentional gender bias that could limit aspirations and expectations. An independent evaluation showed increased awareness of a more diverse range of possible roles for girls and boys, for themselves and others, as well as enhanced critical ability to challenge gender stereotypes. For example, the share of 7- to 11-year-olds reporting that nursing is ‘for everyone’ rather than ‘for boys’ or ‘for girls’ increased from 35% to 71%. The share of boys reporting that they could be a teacher increased from 24% to 42%, while that of girls reporting that they could be a footballer rose from 36% to 47%. Key drivers of the change included the whole-school approach, the effectiveness of staff training, the appointment of a gender champion in school and the breadth and quality of programme resources (Lifting Limits, 2019). The programme shows that a whole school approach is needed to change gender norms that boys and girls learn from a young age.

GENDER BALANCE AND DIVERSITY IN TEACHING AND MANAGEMENT FORM A KEY COMPONENT OF GENDER EQUALITY IN EDUCATION

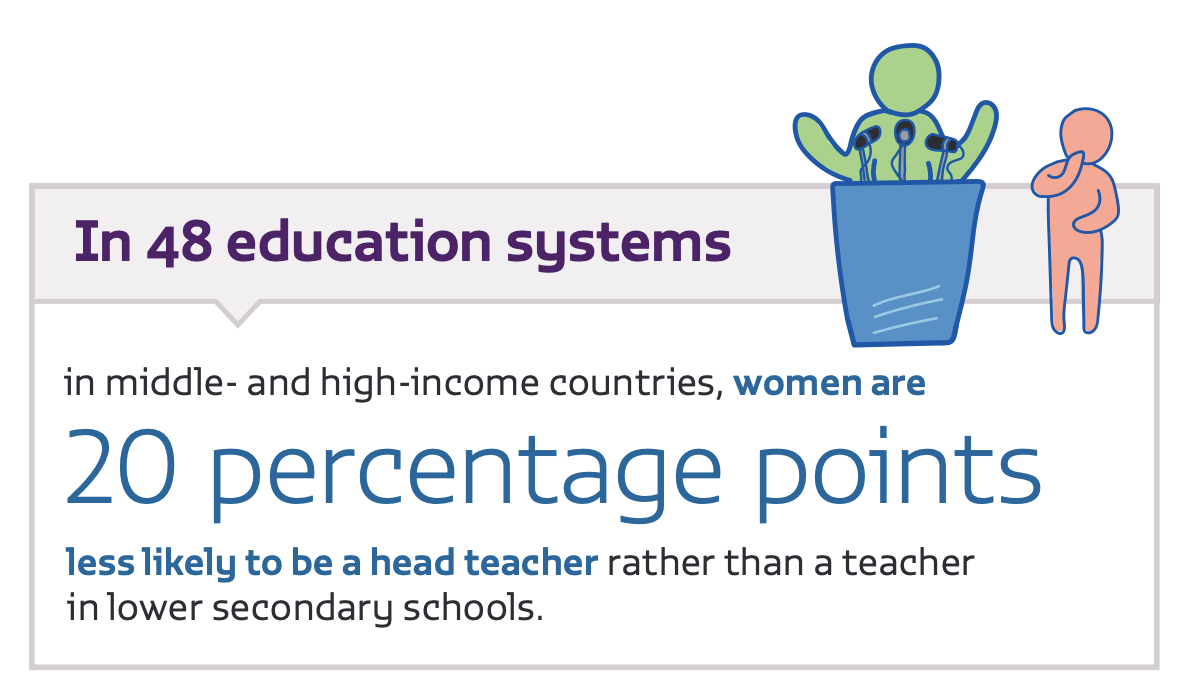

Gender representation in teaching and education management positions is characterized by high gender segregation. Women are over-represented among teaching staff at lower education levels, while their presence is markedly lower in upper secondary and tertiary education (vertical segregation). Women are also under-represented in certain fields of study, notably traditionally male-dominated vocational programmes and STEM (horizontal segregation). The same is true in school management and education policymaking and decision-making positions.

Globally, 94% of pre-primary education teachers were female in 2018. Women represented 66% of teachers in primary, 54% in secondary and 43% in tertiary education. While the share of female teachers in pre-primary education has remained more or less the same since 1995, it has increased at other levels in almost all regions except sub-Saharan Africa, where it decreased in secondary (from 32% to 30%) and tertiary (from 26% to 24%) despite already being the lowest globally at both levels (Figure 15). Even in primary education, the share of female teachers in 2018 was below 30% in Benin, Comoros, Djibouti and Sierra Leone and less than 20% in Togo. Evidence from African countries has shown that girls are more likely to go to school, and parents are more willing to send them to school and keep them there, when female teachers are present, since female teachers are important role models for girls (Haugen et al., 2014).

Figure 15: The percentage of women in teaching positions is increasing worldwide at all levels

Elsewhere, male role models are lacking. In Germany, an initiative to increase the number of men working in early childhood care and education began in 2010, including through the Mehr Männer in Kitas (More men in day-care centres) programme in 2011–13 and Quereinstieg – Männer und Frauen in Kitas (Lateral entry – Men and women in day-care centres), a programme to reorient men seeking to change career, in 2015–20 (OECD, 2019a). While the share of men working in early childhood care and education increased from 3.1% in 2006 to 6.6% in 2019, parity is still far out of reach (Koordinationsstelle Chance Quereinstieg, 2019).

In some countries, diversity has been held back by corrupt hiring practices. In Afghanistan, many teaching positions are reportedly gained through bribery or nepotism. Financial and other obstacles to entry may effectively block candidates from diverse socio-economic backgrounds and can also exacerbate gender disparity. For every 100 male teachers in the country, there are 66 female teachers, and the ratio drops as low as 100:10 in some provinces, including Uruzgan and Zabul. This creates an obstacle to girls’ education in regions where traditional values prohibit girls being taught by men. The Ministry of Education has taken measures to reduce corruption in teacher recruitment (Bakhshi, 2020).

Women are under-represented as senior faculty and in higher education decision-making bodies in many countries. While this reflects women’s history of lower access to education, it is also often a sign of institutional cultures that are neither inclusive nor geared towards broader social and cultural change for greater gender equality. Conventional faculty recruitment processes that reward linear, full-time, uninterrupted academic trajectories contribute to women’s under-representation in senior academic positions, even when women outnumber men as students. Women are more likely to be disadvantaged by norms that fail to recognize competing commitments such as care responsibilities. In 2010, Australia’s Group of Eight leading universities embraced the principle of merit relative to opportunity in faculty recruitment and assessment. The approach encourages a holistic, multidimensional evaluation of academic achievement beyond a narrow focus on publication numbers and considers career breaks, other commitments and individual circumstances (Rafferty et al., 2010).

Official EU guidance endorses incentives and legal sanctions to encourage use of gender quotas and targets in universities (European Commission, 2018). In Ireland, under so-called performance compacts, higher education institutions risk losing up to 10 % of annual state funding if they do not meet certain objectives, including some related to gender equality. Between 2019 and 2021, 45 posts of women-only professorships will be created (European Commission, 2019).

The education sector is not unique in that the interaction of gender with other factors further exacerbates disparity at women’s expense in leadership and management positions. Despite some progress, globally women occupy only 25% of seats in parliament and 36% of senior private sector management positions (World Economic Forum, 2020).

The share of women in leadership positions in schools overall steadily increased in the United States from 25% in 1987/88 to 52% in 2011/12, but the shares of Hispanic head teachers only rose from 3% to 7% and of black head teachers from 8.5% to 10% (Hill et al., 2016). A study of Asian American women in school leadership shows that they had to negotiate their aspirations to leadership and advancement through both gender- and race-related expectations. Many chose a career in school administration because of family responsibilities. While they did not aim for leadership positions when entering teaching, they were encouraged by others, especially mentors who recognized their potential (Liang et al., 2018). Teacher unions have a role to play in promoting gender equality through enhanced social dialogue (avlovaite and Weber, 2019). Lack of teacher diversity can be partly explained by structural factors, reflecting disparity and exclusion within education. Low representation of a particular group among students in higher education or specific fields translates into low representation among graduating teachers, which in turn contributes to low representation in the teaching profession (UNESCO, 2020c). Lack of female teachers in STEM-related subjects has been mentioned as a factor in low female participation in STEM (UNESCO, 2016). But it is also a consequence of low representation of women in STEM-related fields.

FEMINIZATION AND LEADERSHIP GLASS CEILINGS COEXIST IN EDUCATION

Countries have used various strategies to promote vertical and horizontal gender balance in teaching and education management. Case studies from Brazil (Louzano, 2020) and Bulgaria (Delinesheva, 2020) show there is still a long way to go to achieve equality between women and men in the education workforce, despite some positive developments since 1995.In Brazil, no specific policies, programmes or measures to increase the share of women in teaching have been put in place since 1995, since women were already over-represented at all levels except tertiary education. The share of women among university professors increased from 41% in 1999 to 46% in 2018.

In Brazil, for the past 25 years, no women have occupied the position of federal education minister

Feminization of the teaching profession could be expected to lead to greater numbers of women in education leadership positions. This is in fact the case in Brazil, where 82% of head teachers overall were female in 2019. However, the higher the level, the fewer the female head teachers: data from the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey indicate that 77% of lower secondary but 68% of upper secondary head teachers were women. A case study of head teacher selection in lower and upper secondary schools in the Brasilia Federal District, where 76% of teachers are female, found that all candidates for head teacher positions were women in only 11% of the schools. In 75% of the schools, all school leader candidates were men (de Freitas, 2019).

Overall, Brazilian women are as qualified as men, or more so, to occupy leadership positions in tertiary education, yet only 28% of federal university presidents were women in 2018. In addition, women hold 72% of education leadership positions at the municipal level but only one-third of state secretary of education positions. For the past 25 years, no women have occupied the position of federal education minister (Louzano, 2020).

In Bulgaria, the share of women among teachers increased from 81% in 1995 to 85% in 2018, when it ranged from 98% in pre-primary to 80% in secondary education. Women dominate school management positions, accounting for over 96% in pre-primary, 80% in primary and 75% in secondary education. Women also constitute 73% of head teachers, 85% of assistant head teachers with teaching responsibilities and 74% of assistant head teachers without teaching responsibilities.In Bulgarian tertiary education, the share of women holding academic positions increased from 41% in 1995 to 50% in 2018, or from about 8,000 to 11,000. However, a closer look reveals a more nuanced picture. Women accounted for the majority of academic staff in humanities (60%), medicine (55%) and natural and social sciences (54%) in 2015 but for a minority in engineering and technology (34%) despite a significant increase since 2000 (16%). And vertical segregation continues, although there has been considerable improvement. Between 1995 and 2018, the shares of women among assistant professors increased from 44.5% to 53%, among associate professors from 28% to 47% and among professors from 12.5% to 40%. The glass ceiling effect is stronger in decision-making and top leadership positions. Women accounted for 21% of university rector positions in 2018, up from 8% in 2000. Since the establishment of the ministry in 1879, only 5 of 96 education ministers have been women. Since 1995, there have been 4 female ministers, with a total length of service of 2 years and 8 months.

Bulgaria developed a national action plan to meet its Beijing commitments (Bulgaria Government, 1996). In the case of education, it focused on ensuring equal access to education and encouraging vocational education for girls. It made no reference to the feminization of the teaching profession or to male dominance in tertiary education. While the share of women in higher academic positions has increased significantly, leadership positions are still held predominantly by men. In 2017/18, the government carried out a first phase of teacher salary increases (by 15%), aiming to double salaries by 2021. This measure resulted in increased numbers of students in pedagogical faculties, especially in master’s programmes for acquisition of pedagogical qualifications: the number increased by 19% (from 4,866 to 5,775) in 2018/19, although sex disaggregated data are not available (Delinesheva, 2020).

Feminization of the teaching workforce is rooted in traditional expectations about women’s roles in society. Teaching is considered a female occupation, allowing women to fulfil their obligations as wives and mothers. Family environments strongly influence women’s education and professional choices. Men do not want to become teachers because the profession is perceived as typically female, underpaid and with low prestige. Yet women in education face prejudice related to capacity and competence. Gender-related attitudes towards failure and competition also have a role to play in career expectations. In nearly all countries participating in PISA in 2018, girls reported more often than boys that they were afraid of failure, a mindset that could curb their ambition. In over 80% of 79 countries, girls had less positive attitudes than boys to competition (OECD, 2020). Nevertheless, the glass ceiling on women’s advancement in education careers is not seen as part of the education policymaking agenda.